Tango 5

This story took me a while to get down on paper. I'm not precisely sure why, since I've told chunks of it here and there for almost twenty years. Maybe it's because I've never included all the elements togther, or maybe it's because I'm not an engineer and telling this story means distilling a little engineer-speak into relatable english. What it's probably really about is my desire to get it right on behalf of the people I served with - those who lived the story; especially today - 19 years ago, to the day, from what some call the worst day in squadron history. I hope I've done right by you, Broadarrows.

One more thing. This is a story for leaders in every walk of life, not just Sailors, flyers and engineers. To present it to a broad audience, I’ve made an effort to simplify some pretty complicated systems and neutralize some salty Navy lingo so people can understand the situation without a degree in engineering or a sea tour under their belt. If you find yourself pondering that “it was likely particle impact, rather than flow friction”, troubled that I use first names instead of ranks, or lamenting my use of “stairs” instead of “ladder”, please just pause, take a deep breath and read on.

Thank you. On with the post.

There's an aircraft model in my study. It's directly in the center of the highest shelf - resting in a place of honor. The model is a wooden one, of the kind routinely presented to Sailors and officers when they depart an aviation squadron to take orders to follow-on assignments. It's a scaled representation of a US Navy P-3C "Orion" - a martime patrol aircraft assigned to Patrol Squadron 62, also known as "VP-62", the squadron I was privileged to lead as its 23rd Commanding Officer. The model accurately represents the markings of the real bird - The letters “LT” (phonetically, “lima tango”) emblazoned on the tail identify the aircraft as Atlantic-based and, specifically, assigned to VP-62. On each side of her nose are the numerals “005”, the last three digits of her Bureau Number - the military aircraft equivalent of your car’s VIN. Broadarrow Sailors and aircrew refer to her as “LT 005” or “Tango 5” for short.

Or, at least they did.

The Orion’s official “sundown”, or removal from the Navy inventory, was accomplished just a few weeks ago, making way for the newer P-8A Poseidon. My former squadron had the honor of celebrating the old girl in Jacksonville, then flying the last one to the “boneyard” at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona.

But Tango 5 was removed from the inventory long before that. 19 years ago to the day, in fact - on July 10th, 2003, when an explosive ball of pure oxygen melted her insides beyond recognition - and came all too close to taking out one of our team.

This is a story about that fire, sort of. It’s mostly about how people responded to the fire in its aftermath. It’s a story of excellence, teamwork, and loyalty; punctuated at the end by a stark failure of leadership. This tale is like a roller coaster - lows to highs to lows, so buckle up.

Culture of Master Craftsmen

All US Navy squadrons are called by some kind of nickname. Some are pretty unique - The Batmen, Pelicans from Hell and Pukin’ Dogs, for example. My first squadron was the Mad Foxes. If you read or listened to my post The Anthrax Crucible, you met the Liberty Bells and Condors.

At ‘62, we were the Broadarrows.

Originating centuries ago as an ownership mark for British government goods, the broad arrow symbol would eventually be used in the American colonies to mark a forest’s strongest, straightest trees - those whose high-quality lumber would be used for the masts of sailing ships. This use inspired the squadron’s adoption of the symbolic broad arrow (now as a single word - Broadarrow), along with the descriptive language “Master Craftsmen of Trade”, which still appears on the hangar wall and squadron challenge coins.

Staffed by a combination of active duty and reserve Sailors, the Broadarrows were one of the seven squadrons that made up the Navy’s Reserve Patrol Wing. Equipped with the latest technological upgrades to the P-3C Orion, the Broadarrows were envied as the jewel of the Wing.

And it wasn’t just about the equipment. In addition to flying the same new versions of the P-3C as their active duty counterparts, the Broadarrows’ location in the maritime patrol Mecca of Jacksonville, Florida provided the squadron with a steady stream of the Navy’s best flyers, maintainers and support personnel to recruit from as those folks left active duty to pursue civilian careers and continue part-time military service in the Reserve. Jacksonville is home to the only P-3C Fleet Replacement Squadron, or FRS, where flyers, technicians and mechanics get trained by a hand-picked staff of instructors and evaluators - the best performers from across the Fleet, so it’s a much sought after assignment for the active duty folks. This situation meant there was a heavier concentration of maritime patrol talent at VP-62 than at any other squadron - active or reserve - in the entire Navy.

I had served as a Broadarrow earlier in my career and, after subsequent tours of duty with other squadrons, knew the admiration and contempt in which Broadarrows were held by counterparts operating in less beneficial circumstances. When I received my orders to report as Executive Officer (XO), or second-in-command, then fleet-up to Commanding Officer (CO) a year later, I was over the moon. For any Navy officer, Command is the pinnacle of professional achievement and there was no more desirable command in my part of the Navy than command of the Broadarrows.

In fact, the Broadarrows boasted a long succession of top leaders. The CO I would serve as XO was Bryan Quigley, an officer of sterling reputation, “Quigs” was a Reservist - an airline pilot by day, commuting from Virginia. As a full-time guy, I would be his daily eyes and ears at the squadron. We developed a strong mutual trust that allowed us to work well as a team - an advantage we would rely on heavily in the days ahead.

The commanding officers preceding Quigs, and those who would follow me, were also top-notch. The legacy of excellence at VP-62 led to a history of strong performance, a deep sense of organizational pride, and a culture of doing things the right way.

Fire - July 10, 2003

July 10th was a hot, humid Thursday in Jacksonville; not particularly different than any other. You could set your watch by the 2:00 pm thunderstorms there, and it was feeling like today would be no exception.

Aircraft bureau number 163005, or Tango 5, was nearing completion of a periodic “Phase” maintenance cycle. Maintenance Control was being run that day by Bob Waters and Freddy Pacheco, two of the squadron’s top “Chiefs” - seasoned senior managers who run the day to day operations of the Navy. They met with the shop supervisors and asked for an all-hands effort to get Tango 5’s phase complete. After reviewing the paperwork and getting everything in order, they directed Broadarrow technicians Louise Greene and Shawn Yates to service the aircraft’s oxygen system. Shawn would handle the external oxygen cart, while Louise performed and monitored the servicing in the cockpit.

Pretty much business as usual at VP-62.

Meanwhile, I was “topside” - upstairs in the administration spaces of our segment of the large multi-bay hangar we called home - reviewing a stack of officer performance evaluations, or fitness reports. This was a ritual performed twice every year - in the designated month for each officer rank, and whenever the squadron changed commanders. In two weeks, I would move into that seat with the pomp of a Navy Change-of-Command ceremony, but right now it was my job to make sure they were correct, complete and ready for Quigs to sign and debrief on his way out.

It was pretty tedious work - requiring focus - so I was absorbed in the task.

Below me, on the first floor, was the “hangar deck”, where all the aircraft maintenance happened. Two enormous sliding doors opened up to the flight line, where squadron aircraft were meticulously lined up waiting their turn to be either flown or worked on. Just outside those huge open hangar doors, Shawn stood by the bottle that supplied Tango 5 with a fresh supply of pure oxygen, and Louise was kneeling in the aircraft’s cockpit, completing her tool inventory after a routine, and successful, O2 servicing.

Then she heard it.

Lessons learned from the loss of two P-3s to oxygen fire - a Royal Australian Air Force plane in 1984 and a US Navy bird in 1998 - were drilled into Navy technicians who serviced aircraft oxygen. They were trained to recognize the tell-tale sound of an impending oxygen explosion - a “pop”, like a rubber band stretched to the snapping point. If you heard it, there was only one course of action - RUN!

Louise’ training kicked in instinctively. She left her tools behind and ran toward the aircraft exit, about 45 feet away. As she cleared the cockpit, a black-orange ball of flaming oxygen emerged behind her, billowing down the “tube” of the aircraft’s interior, instantly melting everything in its path - the same path Louise was on. The only way out. Louise was literally running for her life.

““It’s oxygen. You can’t put out an oxygen fire until the oxygen is gone.“”

Back topside, Jim Mendoza, our senior Sailor or Command Master Chief, ran toward my office wild-eyed and beat loudly on my doorframe.

“Tango Five is on fire!”

I don’t recall rising from my chair or stepping around my desk, My brain was working to take this in and process what was happening. Sheer adrenaline drove my legs to carry me into the hall and down the stairs. As we burst through the large metal door at the bottom of the stairwell, Jim first and me hot on his heels, we looked through the open hangar bay and saw it. A hard knot clinched in the pit of my stomach.

There was Tango 5 with an enormous black plume of smoke billowing from her cockpit. The NAS Jacksonville fire department had just arrived, and firefighters were dragging hoses around trying to figure just how they were going to turn them on an aircraft that was burning itself from the inside, out. An ambulance was looping around Tango 5’s tail. Inside was Louise Greene, on her way to the base hospital with second degree burns on her right arm, singed hair and eyebrows, and contusions on her leg where the initial blast of exploding oxygen had thrown her against the radar cabinet. She was hurt, but she was alive.

People from other units were gathering like flies at a squadron picnic, taking pictures of the carnage that would quickly find their way onto the fledgling internet - a new phenomenon that would provide armchair analysts with just enough imagery to jump to errant conclusions.

Inside Broadarrow Maintenance Control, everything shifted into automatic. Although everyone hoped it would never happen to them, everyone was trained on how to respond. Aircraft records and logbooks were collected, sealed, boxed and taken to the duty office; NALCOMIS - the platform containing digital aircraft maintenance records - was locked down; and the step-by-step process of mishap reporting went into high gear. The Navy would get to the bottom of whatever happened here through an exhaustive investigation, and the evidence had to be preserved - pristine and unaltered.

After too much time watching firefighters and hoses dance at the foot of the unrelenting black plume, I pulled out my cell phone to give Quigs the bad news. It was the first of several calls I’d make that afternoon to high-ranking officers with skin in the game. Everyone had the same question.

What the hell happened?

Focus

Louise was home recovering. Every Broadarrow was glad we hadn’t lost her that day. As Bob Waters put it “the Navy could buy another airplane”. Jim Mendoza had given Louise all the time she needed to recover and return to work.

It had been a few days since the fire, and today was “FOD walkdown” - a weekly ritual that brought everyone in the squadron - cooks, typists, technicians, aircrew … everyone, to the flight line to walk across our little piece of it looking for anything that could cause “FOD” or Foreign Object Damage. The engines of a P-3C Orion are made to suck in air. Anything they suck in besides air can severely damage the turbines inside and debilitate the engine; so we queue up and walk the flight line looking for screws, dimes, keys, paperclips … anything that might accidentally get sucked up into an intake.

Lining up as a unit and looking across our flight line was normally inspiring - a perfect formation of the Navy’s most advanced anti-submarine aircraft, entrusted to us for their maintenance and operation in the defense of freedom. I usually loved FOD walkdown. Today, though, FOD walkdown meant diverting our collective gaze around and beyond our biggest punch in the gut - a charred hulk, unable to be moved until the salvage engineers and safety investigators said it was clear to do so. Well, we’d just have to step around her and get on our way.

“Let’s go” the line supervisor directed, and all of us moved forward, gazing downward in search of the potentially hazardous “FOD” stuff.

As we approached Tango 5, people close to her took their gaze off the ground and looked up at her charred remains, curiously gazing at her burn holes, looking for clues as to what might have caused her to combust, wondering if the squadron was at fault, reflecting on what Louise went through. I felt like I should do something - seize this moment in our shared experience somehow; to find context; to come together; to focus forward.

“OK, HOLD UP!” I shouted to the supervisor. “Everyone fall out.”

I asked the Broadarrows to gather around Tango 5.

“Take a good, long look. Soak it in.” and people did. Some of the team probably thought it an unnecessarily dramatic event, but everyone joined in the experience. I wasn’t feeling pathos or failure. Instead, I felt unity and resolve.

After a respectful, cathartic pause, we lined back up and resumed the walk down; now with everyone’s gaze set resolutely on the task at hand.

Everyone had doubts the day of the fire. Had we messed up? I mean, we’re only human, right? Aircraft fires ALWAYS mean someone messed up, don’t they?

Yet today, in the direct wake of the fire, doubt began to give a little ground back to allegiance.

Investigation

When something goes wrong in Navy aviation, it’s called a “mishap”. When it goes tragically wrong - the kind of wrong that leaves someone dead or strikes an entire aircraft from the Navy’s inventory - it’s called a “Class A mishap”. It didn’t take the Navy Safety Center long to determine the Tango 5 fire to be a Class A mishap.

There is no more invasive, exhausting, tedious, uncomfortable morale kill than a US Navy Class A mishap investigation. For months, people who you didn’t know a day ago question your integrity, cast doubt on your professionalism, look for chinks in your armor, go through your trash and explore the depths of your training records. They ask you questions then, from your answers, calculate how much sleep you got last night (not enough?). They dig to see if someone may have touched the mishap aircraft at any point in the past without current qualifications (Is that a valid signature?) and they compare the stories of people sequestered, then questioned independently.

The process takes months, providing plenty of time for rumors, second-guessing and armchair quarterbacking to permeate the Navy aviation community.

All eyes were on the Broadarrows, and the “scuttlebutt” that ran through the hangar was predictably prejudicial.

“The f#$%ing reserves had the Auxiliary Power Unit running while they were servicing the oxygen, for Pete’s sake!” was a common accusation. “Unbelievable!”. And it would have been, were it true. Servicing oxygen while simultaneously running an auxiliary engine would have been an act of gross maintenance malpractice. Tango 5’s APU access door was visibly open in the pictures that now circulated throughout the aviation community - a sure sign the APU was running - or, as was the case here, removed. The APU wasn’t scheduled to go back in until Tango 5 completed Phase.

Of course, you can’t operate a piece of equipment that isn’t there, but popular criticism didn’t give way to truth back then, anymore than it does now.

Presuming guilt wasn’t unfounded, however. In my Navy career, I’d never seen a Class A mishap investigation that hadn’t uncovered some kind of human error - at least one; someone taking a procedural short cut, neglecting an important step or showing up for work with some kind of documentable shortcoming. Were we immune to that? Probably not. While it didn’t look like we had committed any obvious missteps that day, there would likely be some missteps uncovered that were less obvious. I found myself hoping our mistakes would be of the kind that merely contributed to the mishap, rather than being primary reasons for it.

Stop. What was I thinking? Hope? Hope wasn’t what my team needed from me now. Hope wasn’t what they deserved or expected. In fact, they had already earned the only acceptable response from me - belief in them and visible support for their proven professionalism.

I resolved to believe.

Of course, I’m not claiming perfection; but the Broadarrows were a solid team - hand-picked from the best and brightest in the Navy for this business. We knew what to do and, whether in response to living up to the resulting expectation or denying the haters, we reliably did it. We were well trained, frequently and thoroughly tested, and steadfastly devoted to the excellence described by our “Master Craftsmen” moniker.

It was time to stop hoping and start believing. We had our shit together, and would look forward to the day the rest of the Navy found out just how much.

This wasn’t flippant vanity. It was intentional allegiance - first of the Broadarrows’ guiding principles. As the Broadarrows cooperated with investigators over the course of the next few months, they lived all three of these principles. So would I.

Manifold Check Valve

The investigation into what caused the Tango 5 fire would ratchet up to a whole new level of scrutiny when a new set of analysts - those at NASA’s White Sands Test Facility - were asked for an outside opinion. Yes, actual rocket scientists - some of the world’s best, in fact - would weigh in on what caused the fire that destroyed Tango 5.

To keep this account from turning into a technical description of aircraft oxygen systems design, I’ll boil the issue down quite a bit. NASA’s report includes terms like “poppets”, “oxide layer forms” and “anodized aluminum based alloy”. If you’re into knowing more about the physics of the incident, you can download the report off NASA’s Technical Reports Server. In order to keep this focused on leadership, I offer this simplified version.

In the P-3C oxygen system, pure O2 moves through a manifold check valve, or MCV, at high pressure. key parts of this MCV are made from aluminum - a flammable metal. The precarious situation of pure oxygen being squeezed at high pressure between flammable metal parts is prevented from becoming an inferno by a thin layer of protective silicon.

high pressure oxygen + flammable metal + chaffed silicon = fire

Again, take the link to the NASA report if you’re interested in more of the engineering.

An Unaffordable Solution

As mentioned earlier, Tango 5 wasn’t the first Orion aircraft lost to oxygen fire. She was the third, so it was clear that there was something imperfect about the system’s design. In fact, the Navy’s inventory of aircraft parts already included a manifold made from Monel - a fire-resistant nickel alloy. These Monel manifolds were making their way into the fleet as replacements, but the cost of replacing them in all P-3s across the fleet was too expensive.

More expensive than the loss of an operational aircraft? You might reasonably query.

(RAAF bird lost in 1984, bearing similar burn marks to Tango 5)

As it turns out, the first two incidents included some of what are referred to in aviation safety as “human causal factors”. If people were to blame, then the risk of another fire could be mitigated with better training, tighter procedures and closer supervision - all much more affordable than the material solution afforded by a complete retrofit of all operational birds with the Monel manifold.

The only way to completely mitigate the threat of another fire was to replace the flawed design; and the only way the Navy was ever going to spend that kind of money was if the design - and the design alone - could be identified as the cause of a mishap. Only an investigation with zero human causal factors would get it done, and the odds of that were, as discussed earlier, historically slim.

Triumph

The day finally came when the investigation was complete and I was to receive the debrief of the Navy Safety Center’s official findings. As the meeting approached, I believed.

The Broadarrows took care of business.

And everybody won.

The NSC’s final report listed material failure as the primary cause of the incident, a finding eventually backed up by NASA’s rocket scientists from White Sands, with no human causal factors - none. It’s impossible to overemphasize just how rare that is. Nonetheless, the Broadarrow team pulled it off. We were vindicated; and now the rest of the Navy knew.

In fact, the rest of the Navy had cause to celebrate. Those flying the P-3 would now fly much safer as the Navy ran out of reasons to delay a complete fleet retrofit to Monel MCVs. In fact, both the US and Canadian fleets were retrofitted over subsequent couple of years.

Safer birds, brought to you by the men and women of VP-62 - the Broadarrows, and almost everyone was happy about it.

Betrayal

As one of the squadrons comprising the Navy’s Reserve Patrol Wing, VP-62 leadership would participate in the annual Wing Conference, held that year at Naval Air Station Key West, Florida. One of the highlights of this conference was announcement of the annual Wing-wide awards. There were awards for tactical proficiency, weapons accuracy, aircraft maintenance, and administrative excellence; but the coveted trophy was the “Battle E” - awarded to the highest overall performing squadron. I, like pretty much every other Commanding Officer, had been gathering intel on how my squadron was stacking up against the others in the preliminary events, and was pretty comfortable where we were - almost ten points ahead of second place. The Battle E would’ve been a great honor any year, celebrated with much fanfare, painted on the noses of the squadron’s aircraft, and even worn on the uniform of each Sailor as an official ribbon; but for a squadron that had been through what we had - and come out vindicated - it would mean even more.

As the conference came to an end, it became time for the capstone event - the announcement of the winners. I sat there with my heart racing, imagining how good it would feel to bring this home, and how much pride it would regenerate on the hangar deck.

We didn’t win everything, and I knew we wouldn’t. We had, however, scored high enough in every award category to either take it home or be the runner up, and no other unit had the consistency of performance to rank so highly in every category. In fact, the only award we had accumulated so far was the Admin Excellence award; but the big “E” was about to be awarded.

To the Minutemen of VP-92 - our sister squadron in Maine and the number two squadron in my covertly gathered point totals.

I couldn’t believe it, but it had happened, and there was only one way for us to not have received that award. The Wing Commander had taken it away from us.

All it took to validate my concern was a quick question to a friend on the Wing staff. Yes, the Wing Commander had 10 discretionary points he could apply to any part of the Battle E scoring, and he used every one of those 10 points to deny the Broadarrows from taking home the Battle E.

“Sir”, I said as I approached the Wing Commander following the announcement, “may I speak with you before you head to the airfield?”

“Sure. I’ll be right out.”

I waited for him outside with my XO Mark Fava who was, no doubt, readying himself to take command sooner than planned after my impending court martial. When he showed up, we stepped around the flow of departing conference-goers.

“Commodore, I know we were positioned to collect the Battle E today. Did you remove us from consideration because of the mishap?”

“Yes”, came his quick response. “I couldn’t justify giving the Battle E to a squadron that had a Class A mishap. The REGNAV [active duty] Wing commanders would never respect that.”

“Well, Commodore, because we had our shit together, every one of those REGNAV Wing commanders now have better safety records in their futures because their squadrons will never have to go through the nightmare we did; and the only reason they’ll have that benefit is because the VP-62 Broadarrows withstood the scrutiny of a Class A Mishap investigation and came out without a single human causal factor.”

“Sir”, I continued, “that fire happened TO us, not BECAUSE of us. You had the opportunity to send a strong signal of support to your highest performing squadron, at a time when we could’ve used it, but instead you let us down. I see that as a leadership failure, sir.”

“In my heart of hearts, I still think you guys made a mistake.”

I can still hear him saying it, attempting to excuse himself for the betrayal.

“Sir, the Navy Safety Center disagrees with you. There’s a report saying as much. I hope you’ll take the time to read it.”

Had the NASA report been out by then, I’d have suggested adding that to his reading list as well.

There’s a reason we have exhaustive, objective, impartial investigations of aircraft mishaps. You don’t get to ignore their results just because you don’t have the guts to reward performance against potential criticism.

But the die was cast, the decision made. I flew home seething at the way my boss stole something from my team they earned and deserved to cover his own insecurity. I’m not saying moral courage is easy; but I am saying it’s essential. What I had just experienced brought that point home with a sharp dagger.

Conclusion

When I received orders in 2002 to report as VP-62’s XO, I knew I’d be working for Quigs and, thanks to some fortunate timing involved in selecting squadron commanding officers, I knew who would serve as my XO - Mark Fava. I worked with the two of them to fine-tune a set of guiding principles I had started developing during my command training track. Those principles - Allegiance, Integrity and Mission - neatly created the acronym AIM, perfect for a squadron called the Broadarrows! It led to a challenge and response phrase that captured the impact of living such principles

AIM True, Strike True

Meaning if we lived by our principles every day, or AIM True; we would be accomplish our purpose, or Strike True. At the rate that squadrons turn over command, it’s difficult to leave a lasting legacy. Each new CO puts their policies in place, then the next one does likewise. I had sought to get Quigs, Mark and I on the same page so we could present our squadron with a consistent leadership focus - strength and continuity amidst change.

To this day, now twenty years later, the CO steps to the microphone with “AIM True!” and the Broadarrows respond with “Strike True!”

While it certainly helped to have three consecutive COs espouse these principles, telling this story has convinced me that allegiance, integrity and mission became permanent at VP-62 when they were forged into the Broadarrow ethos by fire.

Epilogue

After this story originally posted, my friend and former Navy colleague Mike Quinlan asked me what I thought were the three biggest leadership take-aways. Mike is a smart, insightful guy; and I think he was suggesting it would be important to include them. So, here y’are, Mike:

Loyalty is a two-way street

If you’ve done the homework, believe you’ll succeed

Moral courage is a leadership necessity. If you’re lacking in it, grow or pass on the opportunity

Acknowledgements

There were many everyday heroes among the Broadarrows, some appeared in this story; many did not. The brief nature of this post and the fallibility of my memory preclude me from giving full credit where credit is due. Had the Broadarrows not been true “Master Craftsmen of Trade”, this would have been an entirely different story if, in fact, it had ever been written at all.

While everyone who wears, or has worn, the Broadarrow patch can take pride in this story, there are a few individuals who appeared in the story and/or contributed to its writing.

Bryan Quigley - The model of quiet, competent leadership, “Quigs” was the CO at the time of the fire and set us on the path to living by our squadron values - Allegiance, Integrity and Mission - through this incident. He’s now Senior Vice President for United Airlines’ Flight Operations.

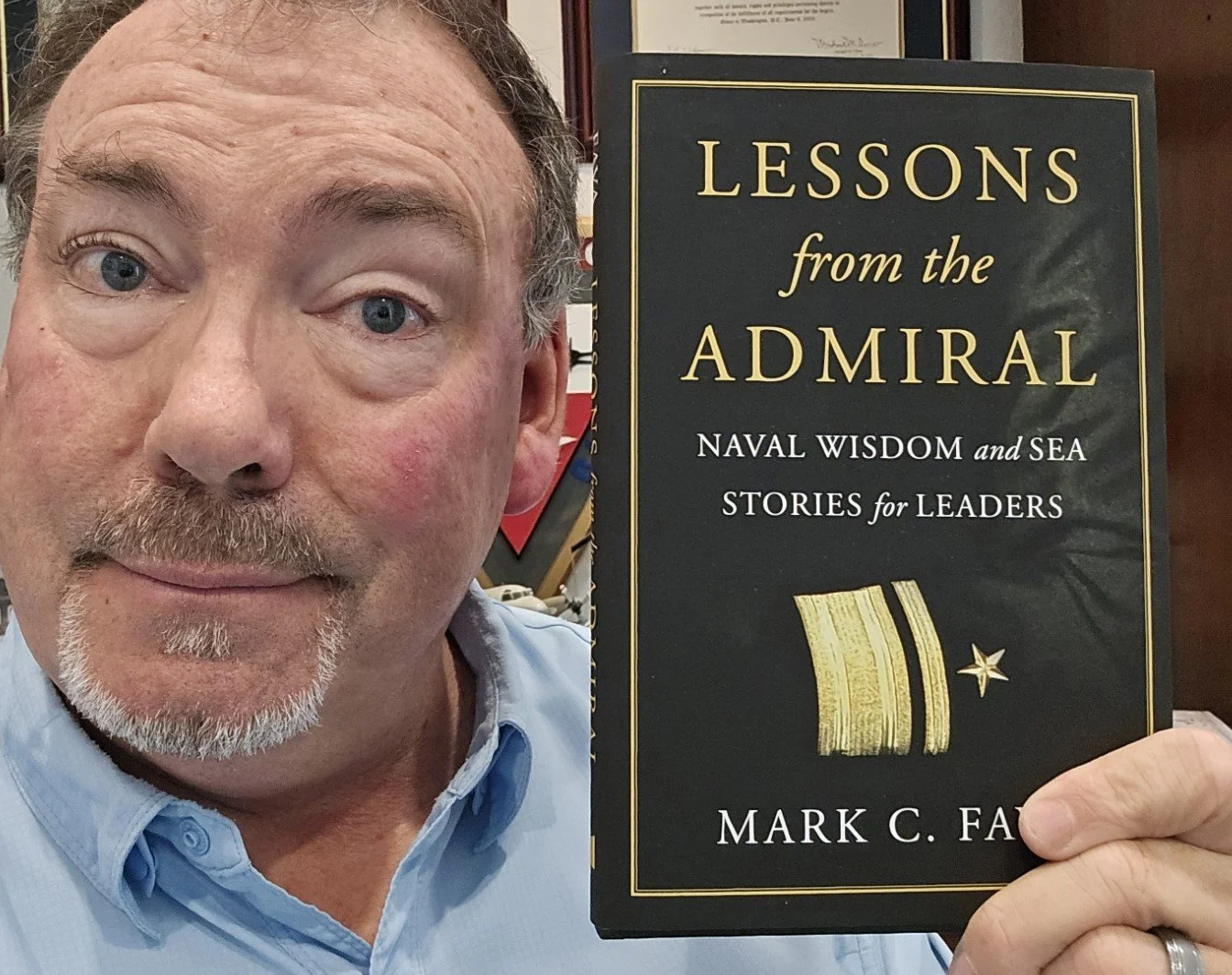

Mark Fava - My XO, successor and lifelong friend, Mark provided wise, measured counsel and visible leadership as we navigated the squadron through the investigation and recovery. He’s now a high-powered aviation attorney with a major aircraft manufacturer.

UPDATE 7/6/25 - Mark is now a best-selling author. His book Lessons from the Admiral details events from his tour as an admrial’s aide that shaped his leadership journey. I highly recommend Mark’s book. It’s excellent. The audio version is read by Mark.

Lessons from the Admiral

Mark’s first book is a winner. I interviewed him about leadership and the book on No Clichés in November 2025.

Jim Mendoza - Broadarrow Command Master Chief at the time of the fire, and another life-long friend. the Tango 5 fire was just one of the many challenges Jim guided me through with sage counsel, steadfast support and unyielding confidence. He’s now retired in Florida, living his best life with Robyn.

Bob Waters - Maintenance Control Chief on duty at the time of the fire. The Broadarrows’ #1 Chief Petty Officer. Now a Team Lead for the P-8A Poseidon at KBR in Jacksonville and the world’s OKest guitar player.

UPDATE 7/6/25 - We lost Bob on 4/16/25 to a medical tragedy when a routine out-patient surgery turned fatal. His Celebration of Life was well attended, and “JustBob” is fondly remembered by many.

Dinner with Bob & Yvette, and Jim & Robyn.

St. Augustine - 2021.

RIP, stallion. We have the watch.

Dean Mercer - Steadfast Broadarrow and a true Master Craftsman. Retired from the Navy the year after the fire and got a job at Titan, where he worked on salvaging Tango 5 and other retired P-3s.

Louise Greene - The Sailor we we’re all happy we didn’t lose that day. She recently retired from the Navy to begin working with police departments in her new field of forensic psychology.

Captain Ian Hawley - Then a young junior officer serving as Aviation Safety Officer for my friend and Naval Academy classmate Chuck Hollingsworth in VP-16, one of the active duty squadrons we shared the hangar with. Ian earned his place as an honorary Broadarrow with his voluntary help over the course of the investigation. His commands include the Navy’s Fleet Logistic Support Wing at NAS JRB Fort Worth, Texas.

Bill Odom - Broadarrow Plankowner (original squadron member) and retiree, Bill worked on the Tango 5 strike and provided the gallery images used in this post.

Featured Image: Australian P-3 Orion like the first one lost to the kind of mishap that claimed Tango 5. photo credit: Photo 189110848 © Ryan Fletcher | Dreamstime.com