New Tricks for the Old Dog - the evolution of executive competence

My first real leadership “job” was as a Tactical Coordinator, or TACCO, in the US Navy’s P-3C Orion maritime patrol aircraft. Think of the role as a kind of orchestra conductor, but instead of musicians playing instruments, a TACCO coordinates technicians operating sophisticated equipment to collect sensor data in pursuit of hidden targets – submarines.

As a rising airborne warrior, I walked with the swagger of someone who knew what he was doing - and I quickly developed the track record to prove it. I wasn’t just competent; I was the go-to TACCO in my squadron - selected as Mission Commander for a top-tier crew and later handpicked to join one of the Navy’s elite training squadrons as an instructor. At that point in my career, competence and confidence rose together in perfect formation.

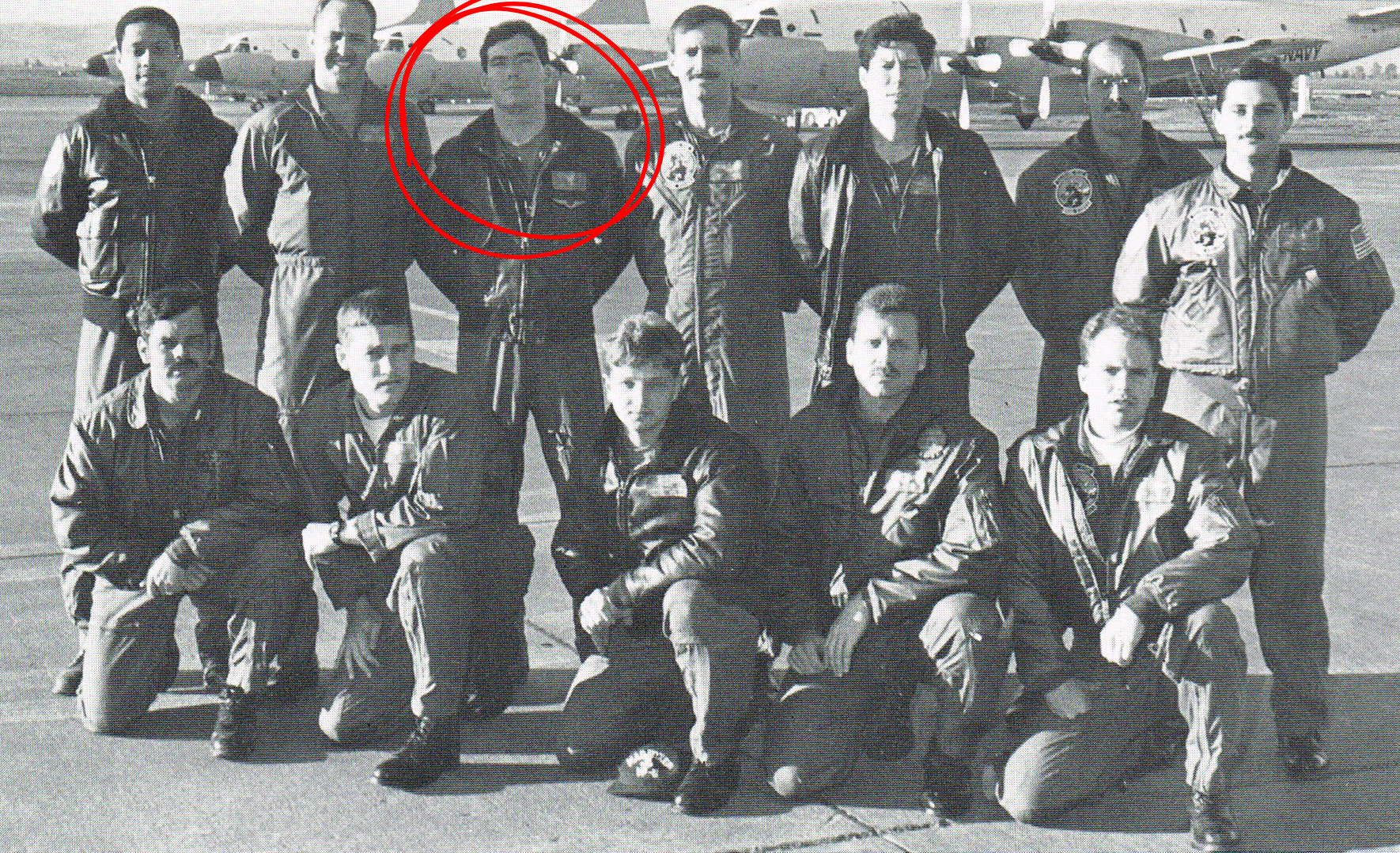

Combat Aircrew (CAC) 4

Although it’s been 40 years since we flew together, I’m still in touch with some of these guys. Sadly, one left this world much too early.

I’m the cocky guy in the red circle.

But something changed during my subsequent career progression to command – the aircraft.

Between my instructor tour and my eventual assignment as a squadron CO, I served a couple of staff tours ashore. Meanwhile, the aircraft itself - the P-3C I had mastered like an extension of my own hands - underwent a major systems upgrade. When I checked back into the community and walked across that tarmac as “the new skipper,” the aircraft waiting for me looked familiar on the outside, but the inside – the “tube” - was a different world. A new suite of avionics. Modified mission systems. Updated tactics.

A new beast.

My pre-command training track had included a brief executive-level transition course on the upgraded platform, just enough to understand the broad strokes; and it wasn’t far into the course that the truth hit me like a catapult shot:

I was no longer technically competent in the machine I was expected to lead others into the sky with.

That’s a sobering moment for any leader.

Up to that point, my identity had been welded to my technical and tactical competence. I was confident because I was good - and everyone knew it. But returning to flight status in command forced me into a new relationship with confidence. I could no longer rely on technical mastery, because I no longer possessed it. What I did have was judgment and experience forged from multiple high-stakes assignments, along with the Navy’s “special trust and confidence” to forge an excellent team.

So I made a choice.

I leaned hard into confidence - not in what I knew, but in how I led.

The Combat Aircrews I led didn’t need me to be the smartest person in the aircraft; they needed me to be the calmest, the clearest, the most centered. They needed a leader whose confidence came not from knowing a panel of instruments, but from values, decision-making rigor, and steadiness under pressure. Overcoming my budding imposter syndrome and embracing my role allowed me to fulfill the responsibilities of command.

We had a successful tour. The crews excelled. We flew safe, effective missions. We won.

To this day, I wish I had squeezed out more time and devoted more energy to rebuilding my technical competence - not because my competence as a leader wasn’t enough, but because I know the difference between leading with the team and leading from behind them. I wasn’t incompetent; I simply wasn’t who I had once been. And I felt that gap.

Patrol Squadron 62 Departing

Addressing Broadarrow Sailors and guests at my outgoing Change-of-Command Ceremony.

This experience taught me about the paradox many top executives eventually face:

The higher you rise, the more competence and confidence begin to diverge.

In your early career years, the relationship is linear. You gain a skill, you get better at it, and your confidence climbs accordingly. By mid-career, you’re running on a well-earned blend of expertise and self-assuredness.

Then when you reach the executive level, something flips.

You become responsible for things you can no longer personally execute. You oversee functions you may not have deep experience in. Technology accelerates beyond your early mastery. Entire domains shift under your feet. And suddenly, the competence that once fueled your confidence becomes insufficient - sometimes even irrelevant - to the complexities of the role.

What replaces it is something entirely different:

Confidence in judgment

Confidence in values

Confidence in your ability to learn fast

Confidence in your team

That’s not false confidence. It’s evolved confidence.

Evolved Confidence

What I learned about competence in the US Navy shaped my leadership as a Red Cross Regional Executive.

I didn’t drive the trucks or staff the shelters, but I led thousands who did.

Still, the gap between technical competence and leadership confidence is real—and often uncomfortable. Some leaders try to mask it. Others ignore it. A few overcompensate with bravado. But the best executives acknowledge the gap, then find the path to lead anyway – to get the job done.

Although I wish I had done more to close my technical knowledge gap before I took command, I’m grateful for what the experience taught me:

Executive leadership often requires us to take the helm when our competence isn’t complete, but our confidence must be.

What I learned in command - and what every executive eventually discovers - is that rising to leadership doesn’t happen the moment you know the most. It happens the moment you’re willing to shoulder the most; because at the highest levels, confidence stops being a product of what you know and becomes a reflection of who you are.

And that kind of confidence will carry your team farther than your personal mastery ever could.

Briefing my final flight in the P-3C and a couple of images from my outgoing Change-of-Command Ceremony.

About the author:

TD Smyers is an Executive Coach and Leadership Consultant. A Bold Leader is his project.

TD holds a Bachelor of Science degree from the US Naval Academy and a Master’s in National Resource Strategy from the National Defense University’s Eisenhower School. He’s led diverse, high performing teams as Commanding Officer of a US Navy aviation squadron and a joint military air base, as well as CEO of major market offices for two global nonprofit organizations and BoardBuild - a nonprofit SaaS company. The Fort Worth Business Press named TD the city’s “Top Nonprofit CEO” in 2019. TD established A Bold Leader after returning from a career pause exploring the Atlantic and Caribbean for three years with his wife, Barbara, on their sailing catamaran, La Vie Dansante.